Researchers from the Extinction and Palaeoenvironmental Reconstruction group have studied the role that major climatic changes and human activity (such as livestock farming) played in the extinction of Europe’s last wild equids (the wild horse Equus ferus, and the wild ass Equus hydruntinus).

The results of the analysis of fossil teeth of wild horses and donkeys that inhabited the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Ice Age reveal that human presence, and not climate warming, may have caused the extinction of Europe’s last wild equids. The international journal “Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology” publishes the results of the study carried out by the palaeontologists of the Dept. of Earth Sciences (UZ) Flavia Strani, Juan de la Cierva researcher, and Daniel DeMiguel, ARAID researcher, attached to the University Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences of Aragon (IUCA) of the University of Zaragoza.

Understanding how large mammals responded to past climate change is crucial to understanding the future of present-day species in the face of global warming, and thereby promoting successful conservation activities to protect current species at risk of extinction.

To date, the hypothesis has been that the reduction of steppe ecosystems (as a consequence of the rise in global temperatures that marked the end of the Ice Age) was the main cause of the disappearance of wild equids, as well as part of the “megafauna” (large mammals that lived during the Ice Age, such as mammoths and woolly rhinos).

Reconstruction of diets

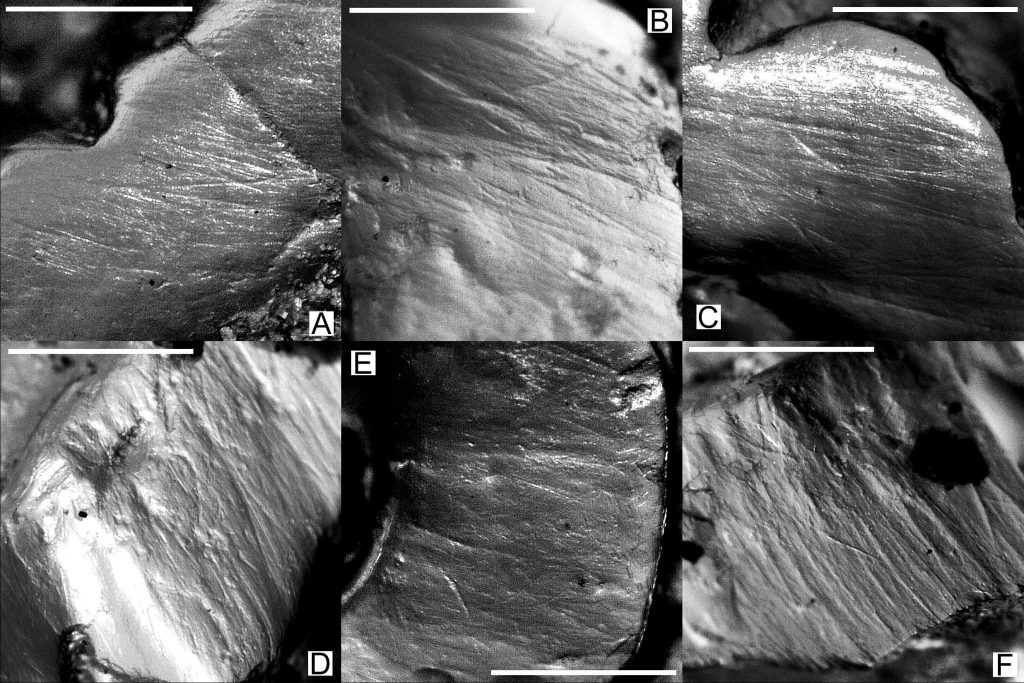

The study was carried out by analysing the fossil teeth of wild horses and donkeys that inhabited the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Ice Age (a period that lasted between 115,000 and 11,700 thousand years ago), in order to reconstruct their diets and thus understand whether they could adapt to the reduction of the steppe biome due to climate change. In particular, the microscopic marks that food leaves on the surface of the teeth during chewing were studied. In this way it was possible to find out what kind of plants the equids fed on, whether it was grasses and herbs in open habitats or fruits and leaves in closed wooded areas.

The results have shown, surprisingly, that these wild equids were able to feed, at least for a time, on plants other than grasses, something that would have allowed them to survive the shrinking of the steppe. Thus, the published work suggests that the disappearance of these wild equids after the Ice Age was not due to a change in climate, but rather to the presence of humans both by introducing livestock that competed for the same resources, and by disrupting the routes that connected the megafauna populations.

Reference: